Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 02/24/2011 in all areas

-

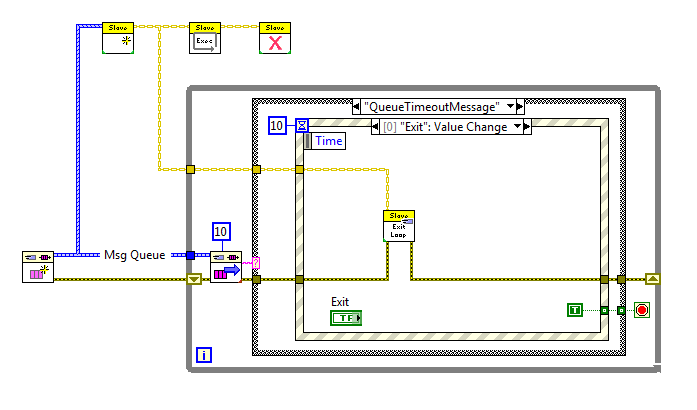

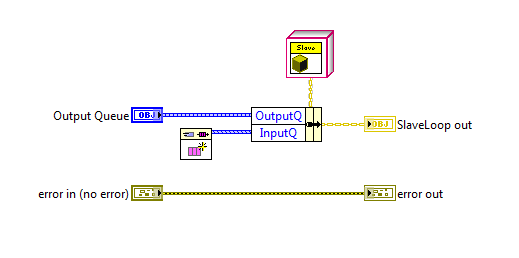

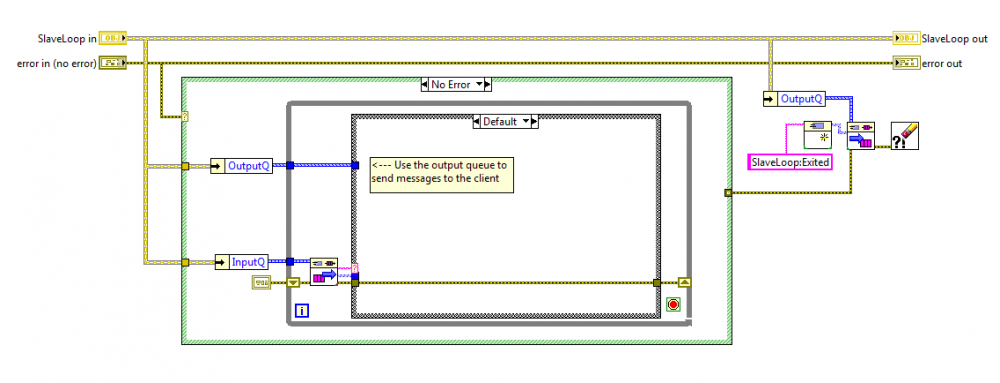

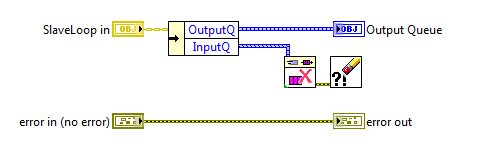

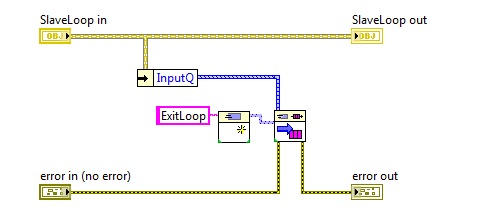

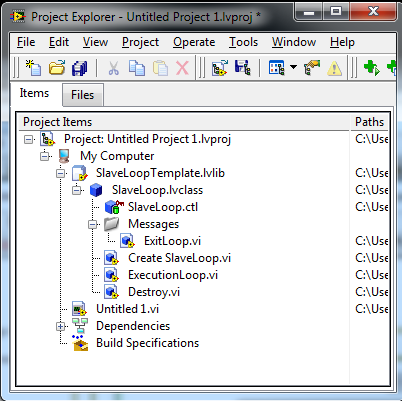

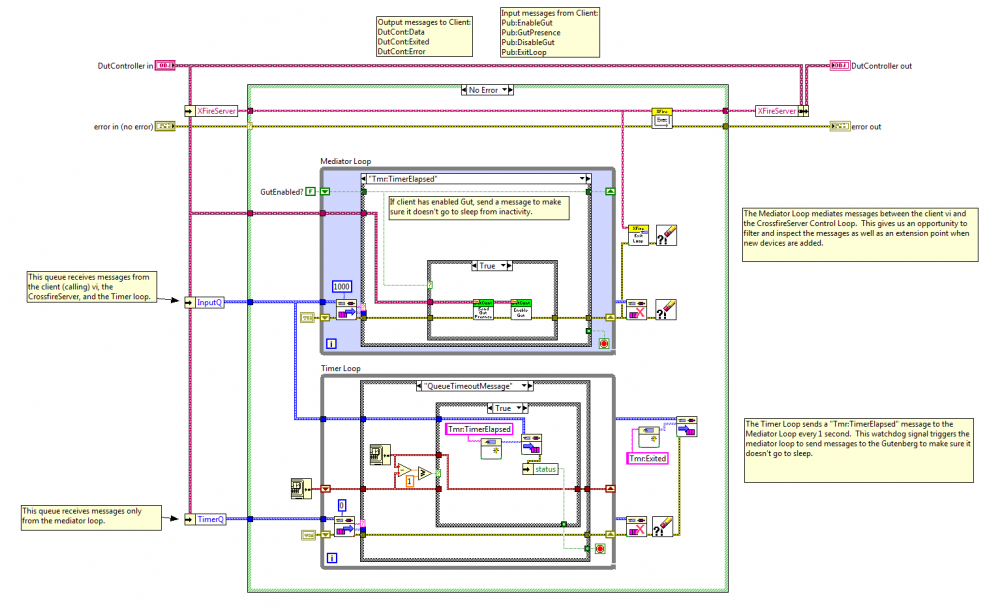

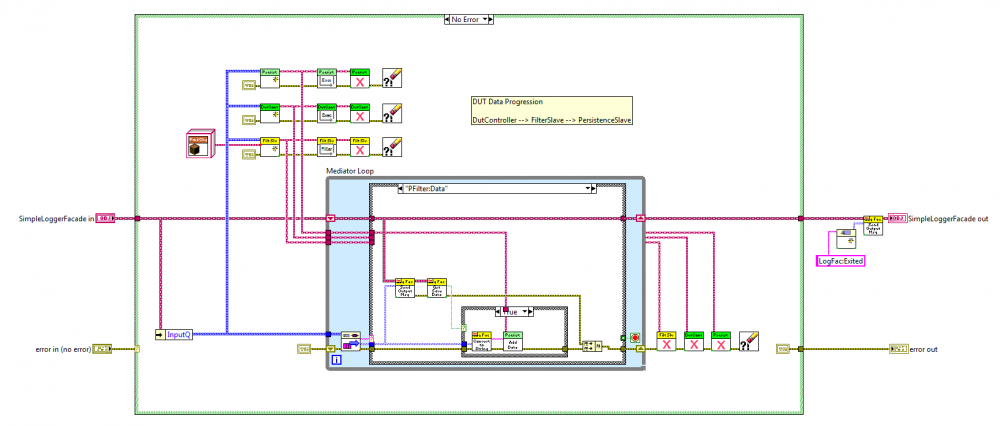

I know some people like to have all their loops visible on the block diagram of the top level vi. I used to do that too, but I found that as the application grew the block diagram got too busy, there was too much to keep track of, and it became very easy to make mistakes. (Not to mention stepping through code is a major PITA.) After a bit I switched over to wrapping my loops in sub vis. That helped, but I ran into issues with that left me dissatisfied as well. I thought I'd share one of the patterns I now use that not only helps me think of my code in components, but also help ensure my components stay decoupled during implementation. It's not particularly unique or innovative, but it might be helpful to someone. I call it a "slave loop object," indicating this object is providing some sort of functionality and sending messages to an "owning" vi. The core slave loop pattern consists of four vis. Three of them, CreateSlaveLoop, ExecutionLoop, and Destroy, execute in parallel to owner's processing loop. The fourth slave loop vi is the messaging vi, ExitLoop. Here's a simple example of what it looks like when used. As expected, the creator method sets up the object's initial conditions and obtains the required resources. At a minimum the object needs an input queue to receive messages from the owning vi and an output queue to send messages to the owning vi. The execution loop can contain anything you want to run in parallel to the owner's main process loop. Usually I'll use some kind of message handler, like this, though I also have used the slave loop pattern to combine several other components and expose a simplified api to the higher level components. (The "facade pattern.") The destroy method is boring and predictable, but here it is. I return the Output Queue to the caller, mainly as a way to indicate to programmers using the slave object that the slave is not releasing the queue. I don't think I've ever used that output for anything but it's there if I need it. Finally, here's the ExitLoop message method. What's this do? Nothing but send a message from the owner's loop to the slave loop executing in the ExecutionLoop method. All new methods I add to the class I'm implementing are messaging methods similar to this. Very simple. The natural question is why bother wrapping all that functionality in a class? Isn't this a lot of extra effort that takes more time and makes the application more complex? Complexity in this context is a matter of perception and depends to a large extent on what you're familiar with. For some this will be more complex until they become familiar with OOP ideas. For others (like me) this is easier to understand because I can tackle parts of the application without needing to comprehend the whole thing. I don't think there's an absolute answer to the complexity question. As for it being a lot of extra effort, no, it isn't. The core of a slave loop class can be hammered out in a few minutes. Less if you have a template class you can copy and paste into your project. That's certainly more time than the 30 seconds it takes to set up a parallel loop on your main BD, but I save a lot of time in other ways. -Since the slave loop's input queue is private, I'm forced to write messaging methods to send it data. This lets me enforce type safety on the message's data because I--the slave loop developer--have control over what data types are exposed on the messaging method's connector pane. If my slave loop has a FormatText message, I drop a string control on the messaging method, wire it up, and I'm done. Since the only way to send that message is by calling the FormatText method, and the FormatText method only accepts string inputs, I don't have to worry about handling cases where the caller might accidentally send an integer. Any mismatched data types are compiler errors instead of runtime errors, so there's a bunch of testing and reviewing I don't have to do. -When using multiple slaves, I don't have to worry at all about accidentally sending a message to the wrong loop. The slave object can only be wired to it's own methods. Again, a mistake here is a compiler error instead of a runtime error, saving me a bunch of time down the road. -The names of the messages are not exposed to the calling vi. Whether you use strings or enums for your message names, you can run into problems if you ever try to change them. Since those names are never exposed or even known outside of the class, it is much easier to make that change and be confident you haven't accidentally broken functionality elsewhere. -Each message to the slave loop is a class method so it is very easy to discover what messages it accepts. I just go to that folder in the project window and look them over. I'll add any pertinant details to the vi's documentation so context help tells me everything I need to know. I don't ever have to dig in the execution loop itself to refresh my memory about what messages to send or what data types to use. All the gory details are encapsulated away and I have a nice clean api to work with. ------------------ As they say, the proof is in the pudding, so here are some block diagram images of execution loops I've created for a project I'm currently working on. The first slave loop is called by my top level UI and is an example of a facade. Notice it has three slave loops of its own. Each of those slave loops were created and tested earlier in the project. Those slave loops were designed to work together, but if I expose them directly to the UI then the UI has to handle all sorts of messages it doesn't really care about. That can be confusing so I created this slave loop object to hide that complexity from the UI. The second execution loop is from the 'DutCont' slave in the above diagram. In this instance I had a slave loop, 'XFireServer,' that has most of the low level functionality I needed, but I needed a watchdog timer to automatically send periodic messages. XFireServer's api is pretty low level, reading and writing to usb pipes, so I also wanted to create a higher level api with methods specifically for the device this tool is testing. This class encapsulates all that functionality and presents it as an easy-to-digest single class with only 7 public methods. As always, comments and critiques are welcome. [Edit Feb 23, 2011 - Added SlaveLoop template class.] Here's a template class with the basic SlaveLoop elements. It's built in LV2010 and does require the LapDog MessageLibrary package, included as part of the zip file. LD SlaveLoopTemplate.zip1 point

-

You can append a random variable to the URL. But first a quick primer on URLs: "http://" is the protocol "www.example.com" is the host name (the computer the web page is on) "/some/place.html" is the path "?random=SomeRandomValue" is the query string The query string is a question mark (?) followed by a set of "variable=value"s, separated by ampersands (&). So if your URL is http://www.a.com/b.html you could make it http://www.a.com/b.html?rand=1234. If your original URL already had a query string (e.g. http://www.a.com/b.html?a=1) then you'd use http://www.a.com/b.h...?a=1&rand=1234. That will force the page to reload because the browser recognizes that could be a different page.. Just remember to use a different random each time. That's a common problem in a number of programming situations not just limited to LabVIEW. The HTTP protocol has metadata saying how long to keep a cached copy around and also metadata to say if a file is newer than another copy. I'm not sure if your web server isn't sending that data, it's sending the wrong data, or LabVIEW isn't respecting that.1 point