All Activity

- Past hour

-

My ZLIB Deflate and Compression in G

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to hooovahh's topic in Code In-Development

They absolutely do! The current ZIP file support they have is basically simply the zlib library AND the additional ZIP/UNZIP example provided with it in the contribution order of the ZLIB library. It used to be quite an old version and I'm not sure if and when they ever really upgraded it to later ZLIB versions. I stumbled over that fact when I tried to create shared libraries for realtime targets. When creating on for the VxWorks OS I never managed to load it at all on a target. Debugging that directly would have required an installation of the Diabolo compiler toolchain from VxWorks which was part of the VxWorks development SDK and WAAAAYYY to expensive to even spend a single thought about trying to use it. After some back and forth with an NI engineer he suggested I look at the export table of the NI-RT VxWorks runtime binary, since VxWorks had the rather huge limitation to only have one single global symbol export table where all the dynamic modules got their symbols registered, so you could not have two modules exporting even one single function with the same name without causing the second module to fail to load. And lo and behold there were pretty much all of the zlib zip/unzip functions in that list and also the zlib functions itself. After I changed the export symbol names of all the functions I wanted to be able to call from my OpenG ZIP library with an extra prefix I could suddenly load my module and call the functions. Why not use the function in the LabVIEW kernel directly then? 1) Many of those symbols are not publicly exported. Under VxWorks you do not seem to have a difference between local functions and exported functions, they all are loaded into the symbol table. Under Linux ELF symbols are per module in function table but marked if they are visible outside the module or not. Under Windows, only explicitly exported functions are in the export function table. So under Windows you simply can't call those other functions at all, since they are not in the LabVIEW kernel export table unless NI adds them explicitly to the export table, which they did only for a few that are used by the ZIP library functions. 2) I have no idea which version NI is using and no control when they change anything and if they modify any of those APIs or not. Relying on such an unstable interface is simply suicide. Last but not least: LabVIEW uses the deflate and inflate functions to compress and decompress various binary streams in its binary file formats. So those functions are there, but not exported to be accessed from a LabVIEW program. -

hooovahh started following How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

-

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

hooovahh replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

😅 You might be waiting a while, I'm mostly interested in compression, not decompression. That being said in the post I made, there is a VI called Process Huffman Tree and Process Data - Inflate Test under the Sandbox folder. I found it on the NI forums at some point and thought it was neat but I wasn't ready to use it yet. It isn't complete obviously but does the walking through of bits of the tree, to bytes. EDIT: Here is the post on NI's forums I found it on. - Today

-

Yes I'm trying to think about where I want to end this endeavor. I could support the storage, and fixed tables modes, which I think are both way WAY easier to handle then the dynamic table it already has. And one area where I think I could actually make something useful, is in compression of CAN frame data and storage. zLib compression works on detecting repeating patterns. And raw CAN data for a single frame ID is very often going to repeat values from that same ID. But the standard BLF log file doesn't order frames by IDs, it orders them by time stamps. So you might get a single repeated frame, but you likely won't have huge repeating sections of a file if they are ordered this way. zLib has a concept of blocks, and over the weekend I thought about how each block could be a CAN ID, compressing all frames from just that ID. That would have huge amounts of repetition, and would save lots of space. And this could be very multi-threaded operation since each ID could be compressed at once. I like thinking about all this, but the actual work seems like it might not be as valuable to others. I mean who need yet another file format, for an already obscure log data? Even if it is faster, or smaller? I might run some tests and see what I come up with, and see if it is worth the effort. As for debugging bit level issues. The AI was pretty decent at this too. I would paste in a set of bytes and ask it to figure out what the values were for various things. It would then go about the zlib analysis and tell me what it thought the issue was. It hallucinated a couple of times, but it did fairly well. Yeah performance isn't wonderful, but it also isn't terrible. I think some direct memory manipulation with LabVIEW calls could help, but I'm unsure how good I can make it, and how often rusty nails in the attic will poke me. I think reading and writing PNG files with compression would be a good addition to the LabVIEW RT tool box. At the moment I don't have a working solution for this, but suspect that if I put some time into I could have something working. I was making web servers on RT that would publish a page for controlling and viewing a running VI. The easiest way to send image data over was as a PNG, but the only option I found was to send it as uncompressed PNG images which are quite a bit larger than even the base level compression. I do wonder why NI doesn't have a native Deflate/Inflate built into LabVIEW. I get that if they use the zlib binaries they need a different one for each target, but I feel that that is a somewhat manageable list. They already have to support creating Zip files on the various targets. If they support Deflate/Inflate, they can do the rest in native G to support zip compression.

-

Wang Jinshuo joined the community

- Yesterday

-

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

ShaunR replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

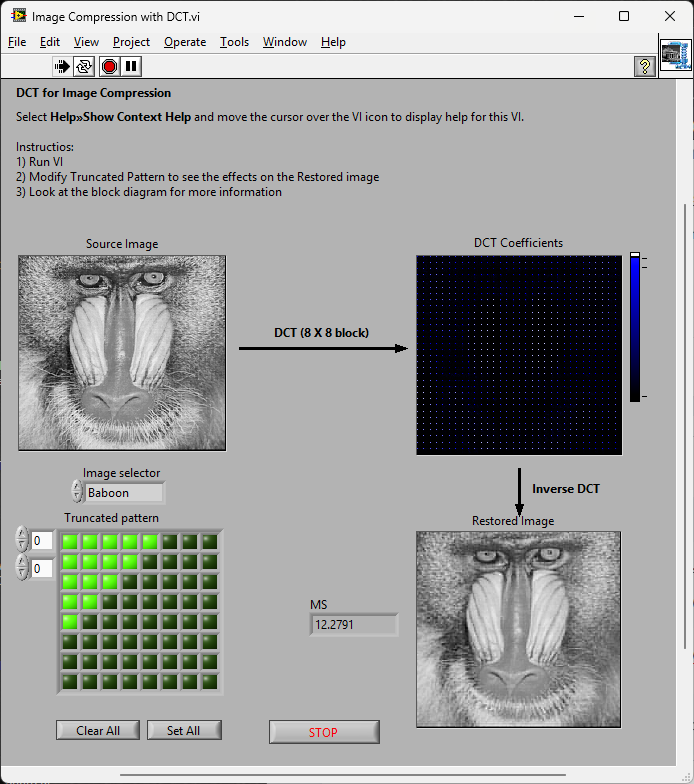

While we are waiting for Hooovah to give us a huffman decoder ... most of the rest seem to be here: Cosine Transform (DCT), sample quantization, and Huffman coding and here: LabVIEW Colour Lab -

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

You make it sound trivial when you list it like that. 😁 -

My ZLIB Deflate and Compression in G

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to hooovahh's topic in Code In-Development

Great effort. I always wondered about that, but looking at the zlib library it was clear that the full functionality was very complex and would take a lot of time to get working. And the biggest problem I saw was the testing. Bit level stuff in LabVIEW is very possible but it is also extremely easy to make errors (that's independent of LabVIEW btw) so getting that right is extremely difficult and just as difficult to proof consistently. Performance is of course another issue. LabVIEW allows a lot of optimizations but when you work on bit level, the individual overhead of each LabVIEW function starts to add up, even if it is in itself just tiny fractions of microseconds. LabVIEW functions do more consistency checking to make sure nothing will crash ever because of out of bounds access and more. That's a nice thing and makes debugging LabVIEW code a lot easier, but it also eats performance, especially if these operations are done in inner loops million of times. Cryptography is another area that has similar challenges, except that security requirements are even higher. Assumed security is worse than no security. I have done in the past a collection of libraries to read and write image formats for TIFF, GIF and BMP. And even implemented the somewhat easier LZW algorithm used in some TIFF and GIF files. On the basic it consists of a collection of stream libraries to access files and binary data buffers as a stream of bytes or bits. It was never intended to be optimized for performance but for interoperability and complete platform independence. One partial regret I have is that I did not implement the compression and decompression layer as a stream based interface. This kind of breaks the easy interchangeability of various formats by just changing the according stream interface or layering an additional stream interface in the stack. But development of a consistent stream architecture is one of the more tricky things in object oriented programming. And implementing a decompressor or compressor as a stream interface is basically turning the whole processing inside out. Not impossible to do, but even more complex than a "simple" block oriented (de)compressor. And also a lot harder to debug. Last but not least it is very incomplete. TIFF support is only for a limited amount of sub-formats, the decoding interface is somewhat more complete while the encoding part only supports basic formats. GIF is similar and BMP is just a very rudimentary skeleton. Another inconsistency is that some interfaces support the input and output to and from IMAQ while others support the 2D LabVIEW Pixmap, and the TIFF output supports both for some of the formats. So it's very sketchy. I did use that library recently in a project where we were reading black/white images from IMAQ which only supports 8 bit greyscale images but the output needed to be 1-bit TIFF data to transfer to a inkjet print head. The previous approach was to save a TIFF file in IMAQ, which was stored as 8-bit grey scale with only really two different values and then invoke an external command to convert the file to 1 bit bi-level TIFF and transfer that to the printer. But that took quite a bit of time and did not allow to process the required 6 to 10 images per second. With this library I could do the full IMAQ to 1-bit TIFF conversion consistently in less than 50 ms per image including writing the file to disk. And I always wondered about what would be needed to extend the compressor/decompressor with a ZLIB inflate/deflate version which is another compression format used in TIFF (and PNG but I haven't considered that yet). The main issue is that adding native JPEG support would be a real hassle as many PNG files use internally a form of JPEG compression for real life images. -

wwm520 joined the community

-

StephJ joined the community

-

Albert0723 joined the community

- Last week

-

choi hong jeong joined the community

-

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

ShaunR replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

There is an example shipped with LabVIEW called "Image Compression with DCT". If one added the colour-space conversion, quantization and changed the order of encoding (entropy encoding) and Huffman RLE you'd have a JPG [En/De]coder. That'd work on all platforms Not volunteering; just saying -

I didn't want to have Excel opened while working on a file so I wrapped OpenXML for LabVIEW https://github.com/pettaa123/Open-Xml-LabVIEW

-

Actechnol joined the community

-

hooovahh started following My ZLIB Deflate and Compression in G

-

So a couple of years ago I was reading about the ZLIB documentation on compression and how it works. It was an interesting blog post going into how it works, and what compression algorithms like zip really do. This is using the LZ77 and Huffman Tables. It was very education and I thought it might be fun to try to write some of it in G. The deflate function in ZLIB is very well understood from an external code call and so the only real ever so slight place that it made sense in my head was to use it on LabVIEW RT. The wonderful OpenG Zip package has support for Linux RT in version 4.2.0b1 as posted here. For now this is the version I will be sticking with because of the RT support. Still I went on my little journey trying to make my own in pure LabVIEW to see what I could do. My first attempt failed immensely and I did not have the knowledge, to understand what was wrong, or how to debug it. As a test of AI progression I decided to dig up this old code and start asking AI about what I could do to improve my code, and to finally have it working properly. Well over the holiday break Google Gemini delivered. It was very helpful for the first 90% or so. It was great having a dialog with back and forth asking about edge cases, and how things are handled. It gave examples and knew what the next steps were. Admittedly it is a somewhat academic problem, and so maybe that's why the AI did so well. And I did still reference some of the other content online. The last 10% were a bit of a pain. The AI hallucinated several times giving wrong information, or analyzed my byte streams incorrectly. But this did help me understand it even more since I had to debug it. So attached is my first go at it in 2022 Q3. It requires some packages from VIPM.IO. Image Manipulation, for making some debug tree drawings which is actually disabled at the moment. And the new version of my Array package 3.1.3.23. So how is performance? Well I only have the deflate function, and it only is on the dynamic table, which only gets called if there is some amount of data around 1K and larger. I tested it with random stuff with lots of repetition and my 700k string took about 100ms to process while the OpenG method took about 2ms. Compression was similar but OpenG was about 5% smaller too. It was a lot of fun, I learned a lot, and will probably apply things I learned, but realistically I will stick with the OpenG for real work. If there are improvements to make, the largest time sink is in detecting the patterns. It is a 32k sliding window and I'm unsure of what techniques can be used to make it faster. ZLIB G Compression.zip

-

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

ensegre replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

You could also check https://github.com/ISISSynchGroup/mjpeg-reader which provides a .Net solution (not tried). So, who volunteers for something working on linux? -

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

Harris Hu replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

This is acceptable. -

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

ensegre replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

As for converting jpg streams in memory, very long time ago I have used https://forums.ni.com/t5/Example-Code/jpeg-string-to-picture/ta-p/3529632 (windows only). At the end of the discussion thread there, @dadreamer refers to https://forums.ni.com/t5/Machine-Vision/Convert-JPEG-image-in-memory-to-Imaq-Image/m-p/3786705#M51129, which links to an alternative WinAPI way. -

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

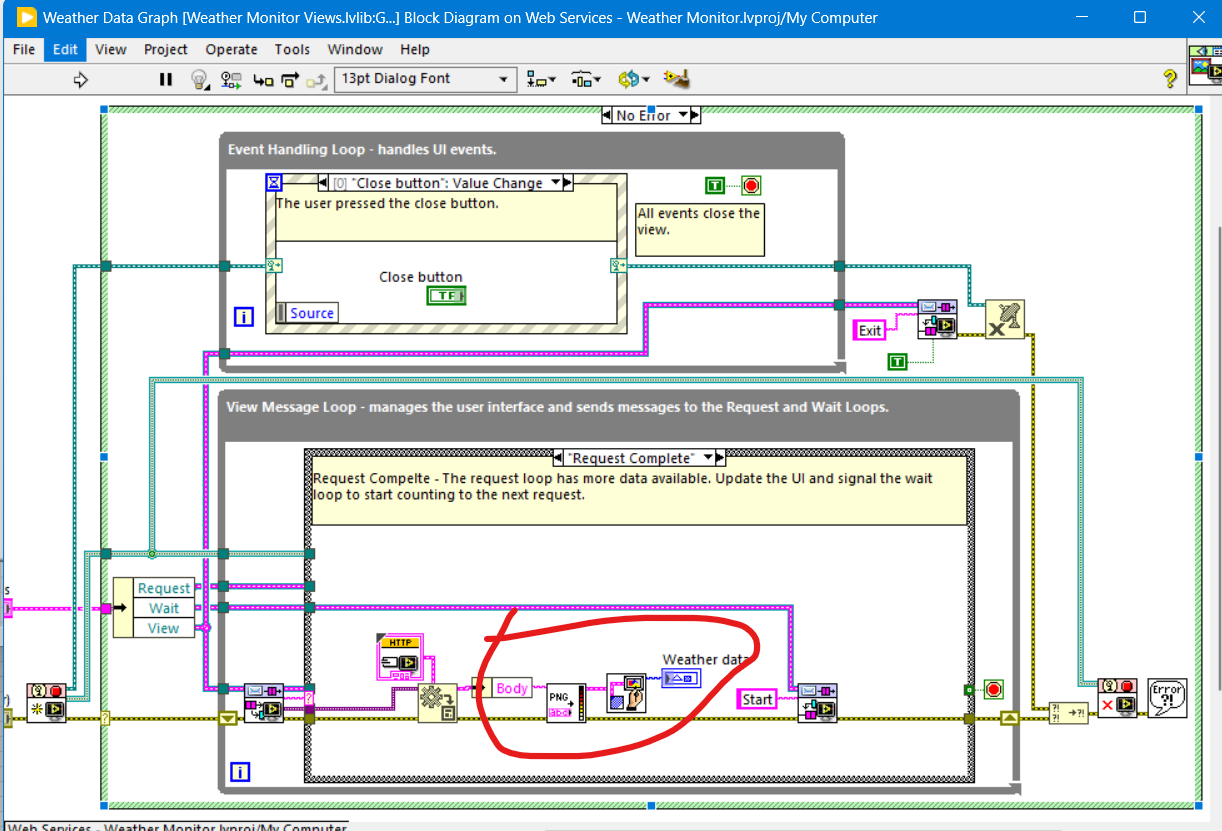

Neil Pate replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

The Weather Station example that ships with LabVIEW shows a bit of this. but the data is not Base64, its just a pure characters, -

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

ShaunR replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

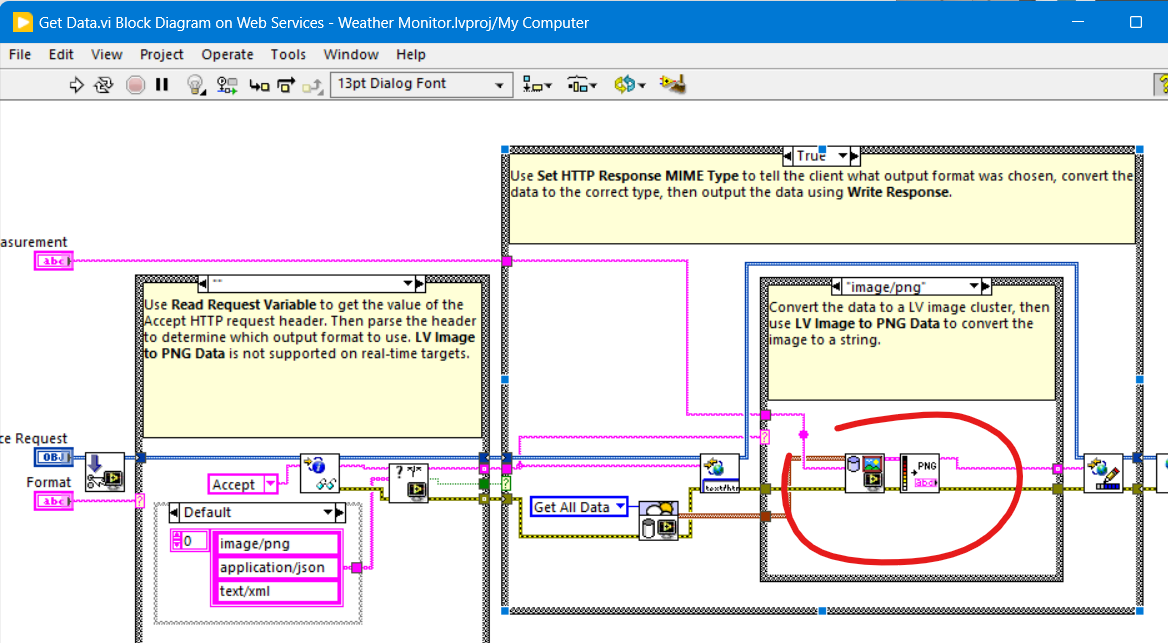

LabVIEW can only draw PNG from a binary string using the PNG Data to LV Image VI. (You'd need to base64 decode the string first) I think there are some hacky .NET solutions kicking around that should be able to do JPG if you are using Windows. -

ensegre started following How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

-

How to load a base64-encoded image in LabVIEW?

ensegre replied to Harris Hu's topic in LabVIEW General

I haven't tried any of them, but these are the first 3 results popping up from a web search: https://forums.ni.com/t5/Example-Code/LabVIEW-Utility-VIs-for-Base64-and-Base32Hex-Encoding-Using/ta-p/3491477 https://www.vipm.io/package/labview_open_source_project_lib_serializer_base64/ https://github.com/LabVIEW-Open-Source/Serializer.Addons (apparently the repo of the code of the previous one) -

I received some image data from a web API in Base64 format. Is there a way to load it into LabVIEW without generating a local file? There are many images to display, and converting them to local files would be cumbersome. base64.txt is a simple example of the returned data. image/jpeg base64.txt

-

The first thing is that you should make sure your VI's diagram and front panels fit a normal screen size and that front panels show up at the center. That way you can collaborate with people with such screens easier, and force yourself to modularize (all that code copied everywhere; make subVIs of it and reuse them(!)) and keep the code tidy. Right now when I open the thing it is huge and off screen, even though my resolution is 2560*1600. This, and the messy non-modularized code will scare off most people from trying to help you as it becomes an unnecessary hassle from the start (dealing with such things instead of an actual logical puzzle is too boring 😉 ). Without an example of the issue you are describing (how does the output file look compared to what you expected e.g.?) and looking at the messy code this first reply now will focus on the style and structure of the code rather than the flagged issue: All the repeated data fetching code e.g. could be reduced to generate an array of fetch parameters and a single for-loop that generates the fetch commands and fetches the data - and outputs an array of the results. If there is a fetch command that avoid having to fetch one parameter at a time I would use that instead as well to eliminate the overhead of each request, otherwise it may sum up and limit your fetch rate....Even better; use a fecth that returns the histroy of multiple items instead of fetching one sample of one item at a time....(I do not know if the API offers this though). Timing-wise you have everything in one huge loop and there is nothing to ensure that it actually runs at the given rate (If you want a loop to run once a second e.g. you have to make sure the code inside it does not take more time to execute and at a minimum you should replace the wait function with a Wait Until Next ms Multiple. Split the code into separate loops and/or VIs that run in parallell instead, making sure each diagram or at least each loop is small enough to be seen on a normal display, allowing the user to get an overview at least vertically, some horisontal scrolling to follow the data flow might sometimes be OK. There are a lot of designs patterns that might be suitable for your code (Producer-Consumer, QMH etc) , but just separating the DAQ (REST Client) bit from the user interface handling e.g. is a good start) I would just skip the signal functions all together. Take the array of values you have fetched and convert it to a spreadsheet string (CSV format e.g.) with a time stamp added to each row and write that to a text file. If you really want to sample multiple times per second you might want to look at circular buffers and only write every now and then. At the level you are now just using the in-built buffers of the charts you already are using might be easier though. Have a look at some of the logging examples included with LabVIEW or available at ni.com to see how those structure the logic.

-

Ranzijie joined the community

-

TWMBK joined the community

-

BiNG joined the community

-

Krystal joined the community

-

From what I can remember, for LV 5.0.x and older RTE (i.e., a loader plus small subset of resources) was included into the EXE automatically during the build process. For LV 5.1.x there was a choice: to include RTE into the build or to use an external RTE. And since LV 6.0 only an external RTE was supposed. I could say more, such a trick is still possible for all modern versions on all three platforms (Win, Mac, Linux). The latest version I tested it on, was LV 2018, but I'm pretty sure, the technique hasn't changed much. I can't remember, from which version NI started to use Visual Studio 2015, but since then each EXE requires The Universal CRT, that is contained in Microsoft Visual C++ 2015 Redistributable. One could install such a distro on a clean machine or copy all these files from the machine, where such a CRT is already installed. Now besides of those the application will also require this minimal subset of folders/files (true for LV 2018 64-bit): On Linux it goes much easier (true for LV 2014 64-bit): For LV 2018 64-bit with a "dark" RTE it also wants And for Mac OS you can embed RTE into the application with this script: Standalone LabVIEW-built Mac Application with Post-Build Action. Of course (and I'm sure everyone understands that), the technique described above, is applicable to very simple 'a la calculator' apps and not very to not at all for more or less complex projects. The more functions are called, the more dependencies you get. If something from MKL is used, you need lvanlys.dll and LV##0000_BLASLAPACK.dll, if VISA is used, you need visa32.dll, NiViAsrl.dll and maybe others, and so on and so forth.

- Earlier

-

I have a LabVIEW VI that opens a REST client and, inside a While Loop, sends multiple HTTP POST requests to read data from sensors. The responses are converted to numeric values, displayed on charts/indicators, and logged to an XLSX file using Set Dynamic Data Attributes and Write To Measurement File, with the loop rate controlled by a Wait (ms). For timestamps I use Get Date/Time In Seconds that links to each of the Set Dynamic Attributes. The charts and displays appear to update correctly, but there are problems with the Excel logging. When the update rate is set higher than 1 sample/s, the saved magnitudes are wrong and are only correct at exact 1-second points (1 s, 2 s, 3 s, etc.); the values in between are incorrect. When the update rate is set to 1 sample/s, the values are initially correct, but after ~30 minutes the effective time interval starts drifting above 1 s. This looks like a buffering, timing, or logging issue rather than a sensor problem. I’ve attached the VI and would appreciate advice on how the VI should be restructured so that the values and timestamps written to Excel are correct and stable over long runs and at higher update rates. I am also attaching the vi where I tried to implement the buffer using the Feedback Node and Case Structure. However there is a problem as the Case Structure is never executed as the buffer at the start is 0. Json_getData_3.vi Json_getData_5_Buffer.vi

-

It just didn't. Like I said. I only got the out of memory when I was trying to load large amounts of data. I suppose you could consider that a crash but there was never any instance of LabVIEW just disappearing like it does nowadays. I only saw the "insane object" two or three times in my whole Quality Engineering career and LabVIEW certainly didn't take down the Windows OS like some of the C programs did regularly. But I can understand you having different experiences. I've come to the conclusion, over the years, that my unorthodox workflows and refusal to be on the bleeding edge of technology, shield me from a lot of the issues people raise.

-

Ok, you should have specified that you were comparing it with tools written in C 🙂 The typical test engineer has definitely no idea about all the possible ways C code can be made to trip over its feet and back then it was even less understood and frameworks that could help alleviate the issue were sparse and far between. What I could not wrap my head around was your claim that LabVIEW never would crash. That's very much controversial to my own experience. 😁 Especially if you make it sound like it is worse nowadays. It's definitely not but your typical use cases are for sure different nowadays than they were back then. And that is almost certainly the real reason you may feel LabVIEW crashes more today then it did back then.

-

Gotta disagree here (surprise!) Take a look at the modern 20k VI monstrosities people are trying to maintain now so as to be in with the cool cats of POOP. I had a VI for every system device type and if they bought another DVM, I'd modify that exe to cater for it. It was perfect modularisation at the device level and modifying the device made no difference to any of the other exe's. Now THAT was encapsulation and the whole test system was about 100 VI's. They are called VI's because it stood for "Virtual Instruments" and that's exactly what they were and I would assemble a virtual test bench from them. Defintely 3). LabVIEW was the first ever programming language I learned when I was a quality engineer so as to automate environmental and specification testing. While I (Quality Engineering) was building up our test capabilities we would use the Design Engineering test harnesses to validate the specifications. I was tasked with replacing the Design Engineering white-box tests with our own black-box ones (the philosophy was to use dissimilar tools to the Design Engineers and validate code paths rather than functions, which their white-box testing didn't do). Ours were written in LabVIEW and theirs was written in C. I can tell you now that their test harnesses had more faults than the Pacific Ocean. I spent 80% of my time trying to get their software to work and another 10% getting them to work reliably over weekends. The last 10% was spent arguing with Engineering when I didn't get the same results as their specification That all changed when moving to LabVIEW. It was stable, reliable and predictable. I could knock up a prototype in a couple of hours on Friday and come back after the weekend and look at the results. By first break I could wander down to the design team and tell them it wasn't going on the production line . That prototype would then be refined, improved and added to the test suite. I forget the actual version I started with but it was on about 30 floppy disks (maybe 2.3 or around there). If you have seen desktop gadgets in Windows 7, 10 or 11 then imagine them but they were VI's. That was my desktop in the 1990's. DVM, Power Supply, and graphing desktop gadgets that ran continuously and I'd launch "tests" to sequence the device configurations and log the data. I will maintain my view that the software industry has not improved in decades and any and all perceived improvements are parasitic of hardware improvements. When I see what people were able to do in software with 1960's and 80's hardware; I feel humbled. When I see what they are able to do with software in the 2020's; I feel despair. I had a global called the "BFG" (Big F#*king Global). It was great. It was when I was going through my "Data Pool" philosophy period.

-

One BBF (Big Beauttiful F*cking) Global Namespace may sound like a great feature but is a major source of all kinds of problems. From a certain system size it is getting very difficult to maintain and extend it for any normal human, even the original developer after a short period. When I read this I was wondering what might cause the clear misalignment of experience here with my memory. 1) It was ironically meant and you forgot the smiley 2) A case of rosy retrospection 3) Or are we living in different universes with different physical laws for computers LabVIEW 2.5 and 3 were a continuous stream of GPFs, at times so bad that you could barely do some work in them. LabVIEW 4 got somewhat better but was still far from easy sailing. 5 and especially 5.1.1 was my first long term development platform. Not perfect for sure but pretty usable. But things like some specific video drivers for sure could send LabVIEW frequently belly up as could more complicated applications with external hardware (from NI). 6i was a gimmick, mainly to appease the internet hype, not really bad bad far from stable. 7.1.1 ended up to be my next long term development platform. Never touched 8.0 and only briefly 8.2.1 which was required for some specific real-time hardware. 8.6.1 was the next version that did get some use from me. But saying that LabVIEW never crashed on me in the 90ies, even with leaving my own external code experiments aside, would be a gross under-exaggeration. And working in the technical support of NI from 1992 to 1996 for sure made me see many many more crashes in that time.

-

The thing I loved about the original LabVIEW was that it was not namespaced or partitioned. You could run an executable and share variables without having to use things like memory maps. I used to to have a toolbox of executables (DVM, Power Supplies, oscilloscopes, logging etc. ) and each test system was just launching the appropriate executable[s] at the appropriate times. It was like OOP composition for an entire test system but with executable modules. Additionally, crashes were unheard of. In the 1990's I think I had 1 insane object in 18 months and didn't know what a GPF fault was until I started looking at other languages. We could run out of memory if we weren't careful though (remember the Bulldozer?). Progress!

-

Tell that to Microsoft. Again. Tell that to Microsoft. I'm afraid the days of preaching from a higher moral ground on behalf of corporations is very much a historical artifact right now.