-

Posts

3,948 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

275

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Downloads

Gallery

Everything posted by Rolf Kalbermatter

-

So you propose for NI to more or less make a Windows GDI text renderer rewrite simply to allow it to use UTF-8 for its strings throughout? And that that beast would even be close to the Windows native one in terms of features, speed and bugs? That sounds like a perfect recipe for disaster. If the whole thing would be required to be in UTF-8 the only feasable way would be to always convert it to UTF-16 before passing it to Windows APIs. Not really worse than now in fact as the Windows ANSI APIs do nothing else in fact but quite a lot of repeated conversions back and forth.

-

How to input Class type to python node

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to Hello183's topic in LabVIEW Community Edition

It's just an integer value. You can either just pass 0, 1 etc to that parameter or create in LabVIEW an enum that has these values assigned to the individual enum values. What doesn't work?- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

Not really. There are two hidden nodes that convert between whatever is the current locale and UTF-8 and vice versa. Nothing more. This works and can be done with various Unicode VI libraries too. Under Windows what it essentially does is something analoguous to this: MgErr ConvertANSIStrToUTF8Str(LStrHandle ansiString, LStrHandle *utf8String) { MgErr err = mgArgErr; int32_t wLen = MultiByteToWideChar(CP_ACP, 0, LStrBuf(*ansiString), LStrLen(*ansiString), NULL, 0); if (wLen) { WCHAR *wStr = (WCHAR*)DSNewPtr(wLen * sizeof(WCHAR)); if (!wStr) return mFullErr; wLen = MultiByteToWideChar(CP_ACP, 0, LStrBuf(*ansiString), LStrLen(*ansiString), wStr, wLen); if (wLen) { int32_t uLen = WideCharToMultiByte(CP_UTF8, 0, wStr, wLen, NULL, 0, NULL, NULL); if (uLen) { err = NumericArrayResize(uB, 1, (UHandle*)utf8String, uLen); if (!err) LStrBuf(**utf8String) = WideCharToMultiByte(CP_UTF8, 0, wStr, wLen, LStrBuf(**utf8String), uLen, NULL, NULL); } } DSDisposePtr(wStr); } return err; } The opposite is done exactly the same, just swap the CP_UTF8 and CP_ACP. Windows does not have a direct UTF-8 to/from anything conversion. Everything has to go through UTF-16 as the common standard. And while UTF-8 to/from UTF-16 is a fairly simple algorithm, since they map directly to each other, it is still one extra memory copy every time. That is why I would personally use native strings in LabVIEW without exposing the actually used internal format and only convert them to whatever is explicitly required, when it is required. Otherwise you have to convert the strings continuously back and forth as Windows APIs either want ANSI or UTF-16, nothing else (and all ANSI functions convert all strings to and from UTF-16 before and after calling the real function, which is always operating on UTF-16. By keeping the internal strings in whatever is the native format, you would avoid a lot of memory copies over and over again. And make a lot of things in the LabVIEW kernel easier. Yes you LabVIEW needs to be careful whenever interfacing to other things, be it VISA, File IO, TCP and also external formats such as VI file formats when they store strings or paths. You do not want them to be platform specific. For the nodes such as VISA, TCP, File read and Write and of course the Call Library Node parameter configuration for strings, it would have to provide a way to explicitly let the user choose the external encoding. It would be of course nice if there were many different encodings selectable including all possible codepages in the world but that is an impossible task to make platform independent. But it should at least allow Current Locale, UTF-8 and WideChar, which would be UTF-16-LE on Windows and UTF-32 on other platforms. Only UTF-8 will be universally platform independent and should be the format used to transport information across systems and between different LabVIEW platforms. The rest is mainly to interface to local applications, APIs and systems. UTF-8 would be the default for at least TCP, and probably also VISA and other instrument communication interfaces. Current Local would be the default for Call Library Node string parameters and similar. Other Nodes like Flatten and Unflatten would implicitly always use UTF-8 format on the external side. But the whole string handling internally is done in one string type which is whatever is the most convenient for the current platform. In my own C library I called it NStr for native string. (Which is indeed somewhat close to the Mac Foundation type NSString, but different enough to not cause name clashing). On Windows it is basically a WCHAR string, on other platforms it is a char string but with the implicit rule to be always in UTF-8 no matter what, except on platforms that would not support UTF-8 which was an issue for at least VxWorks and Pharlap systems, but luckily we don't have to worry about them from next year on since NI will have them definitely sacked by then.😀

-

I think it should. The old string is in whatever locale the system is configured for and is at the same time also using the existing Byte Array === String analogy. That is usually also UTF-8 on most modern Unix systems, and could be UTF-8 on Windows systems that have the UTF-8 Beta hack applied. There should be another string which is whatever the prefered Unicode type for the current platform is. For Windows I would tend to use UTF-16 internally for Unix it is debatable if it should be UTF-32, the wchar_t on pretty much anything that is not Windows, or UTF-8 which is pretty much the predominant Unicode encoding nowadays on non Windows systems and network protocols. I would even go as far as NOT exposing the inner datatype of this new string very much like with Paths in LabVIEW since as long as it existed, but instead provide clear conversion methods to and from explicit String encodings and ByteArrays. The string datatype in the Call Library Node would also have such extra encoding option changes. Flattened strings for LabVIEW internal purposes would be ALWAYS UTF-8. Same for flattened paths. Internally Paths would use whatever the native string format is, which in my opinion would be UTF-16 on Windows and UTF-8 on other systems. Basically the main reason Windows is using UTF-16, is because Microsoft was an early adopter of Unicode. At the time when they implemented Unicode support for Windows, the Unicode space fit easily within the 2^16 character points that UTF-16 provided. When the Unicode consortium finalized the Unicode standard with additional exotic characters and languages, it did however not fit anymore but the Microsoft implementation was already out in the field and changing it was not really a good option anymore. Non-Windows versions only started a bit later and went for UTF-32 as widechar. But that wastes 3 bytes for 99% of the characters used in text outside of Asian languages and that was 20 years ago still a concern. So UTF-8 was adopted by most implementations instead, except on Windows where UTF-16 was both fully implemented and also a moderate compromise between wasting memory for most text representations and being a better standard than the multi codepage mess that was the alternative.

-

Please also allow for byte arrays, as a prefered default data type. Same applies for Flatten and Unflatten. The pink wire for binary strings should be only a backwards compatibility feature and not the default anymore. As to strings, the TCP and other network nodes, should allow to pass in at least UTF-8 strings. This is already the universal encoding for pretty much anything that needs to be in text and go over the wire.

-

Not a chance in a million years. 🙂

-

Yes it's not completely unlogical, just a bit strange since hexa is Greek and decem is Latin. So it's a combination of two words from two different languages. Currently it is so very much commonly used that it is in fact a moot point to debate. But sedecim is fully Latin and means 16. If you wanted to go fully Greek it would be hexadecadic.

-

It's useful and not a bad idea. Clever I would consider something else 🙂 And it's 7 bits since that was the actual prefered data size back then! Some computers had 9 bits, which made octal numbers quite popular too, 8 bits only got popular in the 70ies with the first microprocessors (we leave the 4004 out of this for the moment) which were all using an 8 bit architecture and that got the hexadecimal or more correctly written sedecimal notation popular. Hexa is actually 6 and not 16!

-

Yes but!!!!! That only works for the 7-bit ASCII characters! If you use another encoding it's by far not as simple. While almost all codepages including all Unicode encodings also use the same numeric value for the first 128 characters as what ASCII does (and that is in principle sufficient to write English texts), things for language specific characters get a lot more complicated. The German Umlaut also have upper and lowercase variants, the French accents are not written on uppercase characters but very important on lowercase. Almost every language has some special characters some with uppercase and lowercase variants and all of them are not as simple as just setting a single bit to make it lowercase. So if you are sure to only use English text without any other characters your trick usually works with most codepages including Unicode, but otherwise you need a smart C library like ICU, (and maybe some C runtimes nowadays( which use the correct collation tables to find out what lowercase and uppercase characters correspond to each other. With many languages it is also not always as easy as simply replacing a character with its counterpart. There are characters that have in UTF-8 for instance 2 bytes in one case and 3 bytes in the other. That's a nightmare for a C function having to work on a buffer. Well it can be implemented of course but it makes calling that function a lot more complicated as the function can't work in place at all. And things can get even more complicated since Unicode for instance has for many diacritics two or more ways to write it. There are characters that are the entire letter including the diacritic and others where such a letter is constructed of multiple characters, first the non-diacritic character followed by a not advancing diacritic.

-

Labview VI 2009 mit der Version 2019 bearbeiten

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to Viviane N.'s topic in LabVIEW General

Posted here as well: https://forums.ni.com/t5/LabVIEW/Labview-VI-2009-mit-der-Version-2019/td-p/4182293 Please mention duplicate posts elsewhere, to help people not duplicate effort. -

Calling PeekMessage() is the solution? I would have to disagree! It's more of a workaround than a solution and clearly only Windows only. Trying to do this for Linux or MacOS is going to bring you in very deep waters! Working within the realms of LabVIEW whenever you can is much more of a solution than trying to mess with the message loop. I'm not sure if you ever used the Windows message queue library, which hooks into the WndProc dispatching for a particular window. It's notorious to only work for certain messages and not give you some of the messages you are interested in since Windows is not dispatching it to that window but some other windows such as the hidden root window. And threading comes into the play at every corner. Windows is quite particular about what sort of functions in its window handling it will allow to be executed in a different thread than the one which created that window. Generally there are many limitations and while it may sometimes seem to work at first, it often breaks apart after making seemingly small modifications to the handling. The whole window handling and GDI system originates from a time where Windows used cooperative multitasking. While they tried to make it more concurrent threading tolerant when moving to the Win32 model, a lot of that was through semaphores that can potentially even lock up your code if you are not very careful. And some functions simply don't do much if they don't match the thread affinity of the object they are supposed to operate on.

-

Can you tell me why you want to call PeekMessage() and not simply do the diagram looping to let LabVIEW do the proper abort handling and what else?

-

It might be, however I'm not aware of a MessagePump() exported function in the LabVIEW kernel. It may exist but without the according header file to be able to call it correctly it's a pretty hopeless endeavor. It definitely wasn't exported in LabVIEW versions until around 2009, I stopped trying to analyze what LabVIEW might export on secret goodies around that time. Besides this is not leaving the work to the user. This loop is somewhere inside a subVI of your library. Can the user change it like that? Yes of course but there are funnier ways to shoot in your own feet! 😝 If someone thinks he knows better than me and wants to go and mess with such a subVI, it's his business, but don't come to me and wine if the PC then blows up into pieces! 😀 I'm not quite sure to which statement you refer with the NI reference. Technically every Win32 executable has somewhere pretty much this code, which should be called from the main thread of the process, the same that is created by the OS when launching the process and which is used to execute WinMain() int PASCAL WinMain(HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance, LPSTR lpszCmdLine, int nCmdShow) { MSG msg; BOOL bRet; WNDCLASS wc; UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(lpszCmdLine); // Register the window class for the main window. if (!hPrevInstance) { wc.style = 0; wc.lpfnWndProc = (WNDPROC) WndProc; wc.cbClsExtra = 0; wc.cbWndExtra = 0; wc.hInstance = hInstance; wc.hIcon = LoadIcon((HINSTANCE) NULL, IDI_APPLICATION); wc.hCursor = LoadCursor((HINSTANCE) NULL, IDC_ARROW); wc.hbrBackground = GetStockObject(WHITE_BRUSH); wc.lpszMenuName = "MainMenu"; wc.lpszClassName = "MainWndClass"; if (!RegisterClass(&wc)) return FALSE; } hinst = hInstance; // save instance handle // Create the main window. hwndMain = CreateWindow("MainWndClass", "Sample", WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, (HWND) NULL, (HMENU) NULL, hinst, (LPVOID) NULL); // If the main window cannot be created, terminate // the application. if (!hwndMain) return FALSE; // Show the window and paint its contents. ShowWindow(hwndMain, nCmdShow); UpdateWindow(hwndMain); // Start the message loop. while( (bRet = GetMessage( &msg, NULL, 0, 0 )) != 0) { if (bRet == -1) { // handle the error and possibly exit } else { TranslateMessage(&msg); DispatchMessage(&msg); } } // Return the exit code to the system. return msg.wParam; } The message loop is in the while() statement and while LabVIEWs message loop is a little more complex than this, it is still principally the same. This is also called the root loop in LabVIEW terms, because the Mac message loop works similar but a little different and was often referred to as root loop. MacOS was not inherently multithreading until MacOS X, but in OS 7 and later an application could make use of extensions to implement some sort of multithreading but it was not multithreading like the pthread model or the Win32 threading. And this while loop is also often referred to as message pump, and even Win32 applications need to keep this loop running or Windows will consider the application not responding and will eventually make most people open Task Manager to kill the process. This message pump is also where the (D)COM Marshalling hooks into and makes that marshalling fail if a process doesn't "pump" the messages anymore. And the window created here is the root window in LabVIEW. It is always hidden but its WndProc is the root message dispatcher that receives all the Windows messages that are sent to processes rather than individual windows.

-

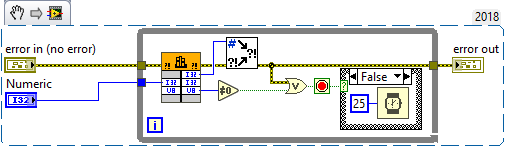

Well, I do understand all that and that is what I have tried to explain to you in my previous two posts, how to work around that. If you for some reason need to execute the CLFN in the UI thread you can NOT use the Abort() callback anymore. Instead you need to do something like this: Basically you move the polling loop from inside the C function into the LabVIEW diagram and just call the function to do its work and check if it needs to be polled again or is now finished. If you put a small wait in the diagram or not depends on the nature of what your C function does. If it is mostly polling some (external) resource you should put a delay on the diagram, if you do really beefy computation in the function you may rather want to spend as much as possible in that function itself (but regularly return to give LabVIEW a chance to abort your VI). The C code might then look something like this: typedef enum { Init, Execute, Finished, } StateEnum; typedef struct { int state; int numm; } MyInstanceDataRec, *MyInstanceDataPtr; MgErr MyReserve(MyInstanceDataPtr *data) { // Don't specifically allocate a memory buffer here. If it is already allocated just initialize it if (*data) { (*data)->state = Init; (*data)->num = 0; } return noErr; } MgErr MyUnreserve(MyInstanceDataPtr *data) { if (*data) { DSDisposePtr(*data); *data = NULL; } return noErr; } MgErr MyPollingFunc(int32_t someNum, uInt8_t *finished, MyInstanceDataPtr *data) { if (!*data) { *data = (MyInstanceDataPtr)DSNewPClr(sizeof(MyInstanceDataRec)); (*data)->state = Execute; } else if ((*data)->state != Execute) { (*data)->state = Execute; (*data)->numm = 0; } // No looping inside our C function and neither should we call functions in here that can block for long periods. The idea is to do what is // necessary in small chunks, check if we need to be executed again to do the next chunk or if we are finished and return the according status. (*data)->numm++; *finished = (*data)->numm >= someNum; if (*finished) (*data)->state = Finished; else usleep(10000); return noErr; } You could almost achieve the same if you would pass a pointer sized integer into the CLFN instead of an InstanceDataPtr, and maintain that integer in a shift register of the loop. However if the user aborts your VI hierarchy, this pointer is left lingering in the shift register and might never get deallocated. Not a big issue for a small buffer like this but still not neat. And yes this works equally well for CLFNs that can run in any thread, but it isn't necessary there. And of course: No reentrant VIs for this! You can not have a reentrant VI execute a CLFN set to run in the UI thread!

-

I somehow missed the fact that you now work on HDCs. HDCs do not explicitly need to be used in the root loop, BUT they need to be used in the same thread that created/retrieved the HDC. And since in LabVIEW only the UI thread is guaranteed to always be the same thread during the lifetime of the process, you might indeed have to put the CLFN into the UI thread. Also I'm pretty sure that Reserve(), Unreserve() and Abort are all called in the context of the UI thread too. But what I'm not getting is where your problem is with this. I believe that the Unreserve() function is always called even if Abort() was called too, but that would have to be tested. In essence it changes nothing though. If you need to call the CLFN in the UI thread, you need to make sure that it does not block inside the C function for a long time, or Windows will consider your LabVIEW app to be unresponsive. And maybe even more important, the LabVIEW UI won't be handled either so you can't press the Abort button in the toolbar either.

-

You completely got that wrong! What I meant was instead of entering the Call Library Node and locking in the DLL function until your functionality is finished, and polling in the C function periodcally the abort condition in the InstanceDataPtr, you would do the looping on the VI diagram and reenter the CLFN until it returns a status done value, after which you exit the loop. Now you do not need to actually configure the Abort() function and could even not configure the Reserve() function but still pass the InstanceDataPtr to your CLFN function. On entry you check that InstanceDataPtr to be non null and allocate a new one if it is null, and then you store state information for your call in there. Then you start your operation and periodically check for its completion. If it is not completed you still terminate the function but return a not completed status to the diagram, which will cause the diagram loop to continue looping. When the user now aborts the VI hierarchy LabVIEW will be able to abort your VI when your CLFN returns with the complete or not complete status. So you don't need the InstanceDataPtr to be able to abort your CLFN function asynchronously. But you still get the benefit of the Unreserve() function which LabVIEW will call with the InstanceDataPtr. In there you check that the pointer is not null and deallocate all the resources in there and then the pointer itself. It's almost equivalent if you would use a shift register in your diagram loop to store a pointer in there that you pass into the function and after the CLFN call put back into the shift register on each iteration, except that when the user aborts the VI hierarchy you do not get a chance to call another VI to deallocate that pointer. With the InstanceDataPtr the Unreserve() function can do that cleanup and avoid lingering resources, aka memory leaks. You could do that for both UI threaded CLFNs as well as any threaded CLFNs, for the first it is mandatory to avoid your function blocking the LabVIEW UI thread, for the second its optional but still would work too.

-

The Callbacks are executed during initialization of the environment (the instant you hit the run button) or when the hierarchy ends its execution. So returning those errors as part of the Call Library Node may be not really very intuitive. As the Reserve() seems to be called at start and not load, it's also not easy to cause a broken diagram. So yes I can see that these errors are kind of difficult to fit into a consistent model to be reported to the user.

-

The scope is supposedly still CLFN local but I never tested that. The InstanceDataPtr is tied to the CLFN instance and that is dependent on the VI instance. As long as a VI is not reentrant it exists exactly once in the whole LabVIEW hierarchy no matter if it runs in the UI thread or another thread. And each CLFN in the VI has its own InstanceDataPtr. If a VI is reentrant things get more hairy as each CLFN gets for each VI instance its own InstanceDataPtr. And if you have reentrant VIs inside reentrant VIs that instantiation quickly can spiral out of reach of human grasp. 🙂 Think of the InstanceDataPtr as an implicit Feedback Node or Shift Register on the diagram. One of them for every Call Library Node. That's basically exactly how it works in reality. Obviously if you run a blocking VI in the UI thread you run into a problem as LabVIEW doesn't get any chance to run its message loop anymore which executes in the same thread. And Windows considers an application that doesn't poll the message queue with GetMessage() for a certain time as being unresponsive. But calling GetMessage() yourself is certainly going to mess up things as you now steal events from LabVIEW and PeekMessage() is only for a short time a solution. So if you absolutely have to call the CLFN in the UI thread (why?) you will have to program it differently. You must let the CLFN return to the LabVIEW diagram periodically and do the looping on the diagram instead of inside the C function. You still can use the InstanceDataPtr to maintain local state information for the looping but the Abort mechanisme won't be very important as LabVIEW gets a chance to abort your VI everytime the CLFN returns to the diagram. The nice thing about using an InstanceDataPtr for this instead of simply a pointer sized integer maintained yourself in a shift register in the loop is, that LabVIEW will still call Unreserve() (if configured of course) when terminating the hierarchy so you get a chance to deallocate anything you allocated in there. With your own pointer in a shift register it gets much more complicated to make the deallocation properly when the program is aborted.

-

Custom subarrays

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to HugoChrist's topic in Application Design & Architecture

It's really unclear to me what you try to do. There is simply no way to create subarrays in external code until now. And there is no LabVIEW node that allows you to do that either. LabVIEW nodes decide themselves if they can accept subarrays or not and if they want to create subarrays or not but there is simply no control about that. Also subarrays support a bit more options than what ArrayMemInfo returns. Aside from stride it also contains various flags such as if the array is considered to be reversed (its internal pointer points to the end of the array data), transposed (rows and colums are swapped meaning that the sizes and strides are swapped), etc. Theoretically, Array Subset should be able to allocate subarrays, and quite likely does so, but once you display them in a front panel control, that front panel control will always make a real copy for its internal buffer, since it can't rely on subarrays. Subarrays are like pointers or reference and you do not want your front panel data element to automatically change its values at anytime except when dataflow dictates that you pass new data to the terminal. And the other problem is once you start to autoindex subarrays, things get extremely hairy very quickly. You would need subarrays containing subarrays containing subarrays to be able to represent your data structure and that is aside from very difficult to make generic also quickly consuming even more memory than your 8 * 8 * 3 * 3 element array would require. Even if you extend your data to huge outer dimensions a subarray takes pretty much as much data to store than your 3 * 3 window, so you win very little. Basically LabVIEW nodes can generate subarrays, auto indexing tunnels on loops could only with a LOT of effort on figuring out the right transformations, with very little benefit in most situations. -

Your problem is that the correct definition for those functions in terms of basic datatypes would be: MgErr (*FunctionName)(void* *data); This is a reference to a pointer, which makes all of the difference. A little more clearly written as: MgErr (*FunctionName)(void **data);

-

I don't quite have a working example but the logic for allocation and deallocation is pretty much as explained by JKSH already. But that is not where it would be very useful really. What he does is simply calculating the time difference between when the VI hierarchy containing the CLFN was started until it was terminated. Not that useful really. 😀 The usefulness is in the third function AbortCallback() and the actual CLFN function itself. // Our data structure to manage the asynchronous management typedef struct { time_t time; int state; LStrHandle buff; } MyManagedStruct; // These are the CLFN Callback functions. You could either have multiple sets of Callback functions each operating on their own data // structure as InstanceDataPtr for one or more functions or one set for an entire library. Using the same data structure for all. In // the latter case these functions will need to be a bit smarter to determine differences for different functions or function sets // based on extra info in the data structure but it is a lot easier to manage, since you don't have different Callback functions for // different CLFNs. MgErr LibXYZReserve(InstanceDataPtr *data) { // LabVIEW wants us to initialize our instance data pointer. If everything fits into a pointer // we could just use it, otherwise we allocate a memory buffer and assign its pointer to // the instanceDataPtr MyManagedStruct *myData; if (!*data) { // We got a NULL pointer, allocate our struct. This should be the standard unless the VI was run before and we forgot to // assign the Unreserve function or didn't deallocate or clear the InstanceDataPtr in there. *data = (InstanceDataPtr)malloc(sizeof(MyManagedStruct)); if (!*data) return mFullErr; memset(*data, 0, sizeof(MyManagedStruct)); } myData = (MyManagedStruct*)*data; myData->time = time(NULL); myData->state = Idle; return noErr; } MgErr LibXYZUnreserve(InstanceDataPtr *data) { // LabVIEW wants us to deallocate a instance data pointer if (*data) { MyManagedStruct *myData = (MyManagedStruct*)*data; // We could check if there is still something active and signal to abort and wait for it // to have aborted but it's better to do that in the Abort callback ....... // Deallocate all resources if (myData->buff) DSDisposeHandle(myData->buff); // Deallocate our memory buffer and assign NULL to the InstanceDataPointer free(*data) *data = NULL; } return noErr; } MgErr LibXYZAbort(InstanceDataPtr *data) { // LabVIEW wants us to abort a pending operation if (*data) { MyManagedStruct *myData = (MyManagedStruct*)*data; // In a real application we do probably want to first check that there is actually something to abort and // if so signal an abort and then wait for the function to actually have aborted. // This here is very simple and not fully thread safe. Better would be to use an Event or Notifier // or whatever or at least use atomic memory access functions with semaphores or similar. myData->state = Abort; } return noErr; } // This is the actual function that is called by the Call Library Node MgErr LibXYZBlockingFunc1(........, InstanceDataPtr *data) { if (*data) { MyManagedStruct *myData = (MyManagedStruct*)*data; myData->state = Running; // keep looping until abort is set to true while (myData->state != Abort) { if (LongOperationFinished(myData)) break; } myData->state = Idle; } else { // Shouldn't happen but maybe we can operate synchronous and risk locking the // machine when the user tries to abort us. } return noErr; } When you now configure a CLFN, you can assign an extra parameter as InstanceDataPtr. This terminal will be greyed out as you can not connect anything to it on the diagram. But LabVIEW will pass it the InstanceDataPtr that you have created in the ReserveCallback() function configuration for that CLFN. And each CLFN on a diagram has its own InstanceDataPtr that is only valid for that specific CLFN. And if your VI is set reentrant LabVIEW will maintain an InstanceDataPtr per CLFN per reentrant instance!

-

Custom subarrays

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to HugoChrist's topic in Application Design & Architecture

Actually arrays (of scalars) normally are allocated as one block. And while LabVIEW internally does indeed use subarrays, there is also a function that will convert subarrays to normal arrays whenever a function doesn't like subarrays. Basically functions need to tell LabVIEW if they can deal with subarrays and unless they explicitly say that they can for an array parameter, LabVIEW will simply convert it to a full array for them before passing it to the function. And the Call Library Node is a function that explicitly does not want subarrays parameters. Theoretically it may be possible but the subarray data structure is more complex than the one that you display in your post. The interface to subarrays is not documented for external tools in LabVIEW, never passed to any external function, interface or data client. It is not trivial to work with, and if LabVIEW would allow that at the Call Library Node interface, EVERY code would need to be prepared that there could be a subarray entry, or there would have to be some involved need for letting a DLL tell LabVIEW that it can accept subarrays for parameter x, z and s, but not for a, b, and c. Totally unmanageable!!! 🤮 So no a Call Library Node will always receive a full array. If necessary LabVIEW will create one! -

Unprintable characters on LavaG

Rolf Kalbermatter replied to LogMAN's topic in Site Feedback & Support

I reported all of them last week. Did not notice at first either but in the last post somehow the link sprang in my eyes and I was first thinking it was a special name for quote marks wondering what that word would mean. 😀 Google quickly taught me that it is some drugs name and from there it was obvious. Then looked at the other 3 before that and saw the same pattern together with a pretty meaningless message. -

You really should learn a little C programming. Because that is what is required when trying to call DLLs. Or hire someone to make the LabVIEW bindings for you! Currently you are sticking around with a pole in a heap of hay to find the needles hidden in there, but having chosen to not only blindfold yourself to make it more "interesting" but also bind your hands on your back. DLL_START is the function pointer declaration and is basically documenting the parameters and return value the function takes. This is almost what you need to use for the import library wizard but not quite. A function pointer declaration is only similar to a function declaration but not the same. The Import Library Wizard however needs a function declaration and it needs to use the same name as what the DLL is exporting, otherwise the wizard can't match the declaration to a particular function. In your example you need to find what function pointer declaration is used for which function. Then you need to translate it to a function declaration. So you have determined that the DLL_START declaration is used for the function pointer for StartGenericDevice() typedef int (*DLL_START) ( DWORD *dwSamplerate ); will then have to be turned into following function declaration: int StartGenericDevice( DWORD *dwSamplerate ); With this the Import Library Wizard does have a function prototype to use for the function exported from the DLL. Now you need to do that also for your other functions in the DLL.

-

Well, if you have the source code for the GenericDevice_DLL_DEMODlg program you may be able to verify that which function pointer is assigned which DLL function. Without that it is simply assuming and things and there is "ass" in the word assuming, which is where assumptions usually bite you in! 😀